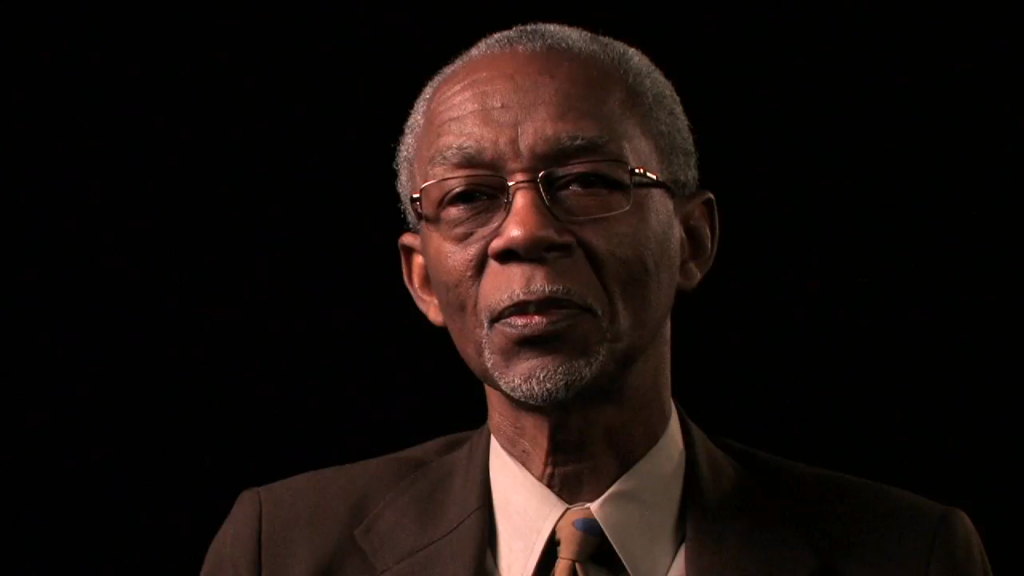

Roger Boykin remembers a city full of musical talent – and why he and others felt compelled to document it 55 years ago

As we celebrate the premiere of We Want The Funk on KERA TV tonight (April 8), we also note another upcoming date: June 22, 2025 marks the 55th anniversary of the South Dallas Pop Festival. The festival sprung from a desire of local musicians Roger Boykin and Wendell Sneed to showcase local bands that were thriving in Dallas clubs. The Soul Seven, The Marcel Ivery Quintet, The Apollo Commanders, Les Watson and the Panthers and others who had been sharpening their skills in clubs for months finally got to share the same stage.

The concert was captured on audiotape, and immortalized in releases of those recordings as well as the 2009 KERA documentary South Dallas Pop. Boykin sat down recently to look back at this concert, which the musicians felt was necessary for their work to be noticed. He recalled a vibrant Dallas music scene that left a legacy larger than the credit it received.

The Blues

What propelled Dallas musicians during the mid-20th century? Boykin said it all goes back to the blues.

“There were so many good blues and jazz musicians around here going back to the ‘40s, ‘50s and on up,” Boykin said. “The influence of the blues out of Texas produced a whole lot of great music. Blues is the underlying and most important element in rock and roll, hip hop and a lot of pop music. (And) a lot of it really did come from the Dallas-Fort Worth area and North Texas in general. Just to give an example, T-Bone Walker lived here, and he influenced B.B. King; of course, B.B. King probably influenced every blues guitar player in the world when he started recording in the 1950s.”

North Texas proved to be a helpful talent incubator – yet many who started here got famous elsewhere.

“A lot of people don’t know Sly Stone was born in Denton.” Boykin said. “Fort Worth has Cornell Dupree, the guitar player, and “King Curtis,” Curtis Ousley. When King Curtis and (Dupree) moved to New York, they became vital members of Aretha Franklin’s group, and they were with Atlantic Records. Dupree played on the best album that Donnie Hathaway recorded, Extension of a Man. He’s playing guitar on there.”

Boykin spent time touring with another luminary to come out of the area, Corsicana saxophonist David “Fathead” Newman.

“Fathead Newman played for years with Ray Charles,” Boykin added. “He’s from here. I actually toured with him for a year and made an album called Front Money.”

As if influencing B.B. King and working with Ray Charles weren’t enough, North Texas helped mentor Charlie Parker as well.

“One of the main influences from around here was Russell “Buster” Smith,” Boykin recalled. “Buster Smith made his bones initially in Kansas City, and he actually wrote arrangements and played with Charlie (Parker). They were close.

“Buster Smith was one of the most important figures in jazz history because of what he did in Kansas City. But then he moved back here and influenced a lot of people.”

The Ukelele

Boykin had a passion for music dating back to singing in his church choir, but the seeds of his instrumental career started with a holiday gift.

“When I was 9 years old, I got a ukelele for Christmas,” Boykin said. When I was 15, I got a guitar. Six months later, I was in the music association. I’d played ukelele for five years, so switching to the guitar was not that difficult because the left-hand/right-hand coordination was there. I already had a concept, and I had been listening to blues from about age nine or ten going up until I started playing it and singing it in high school. I participated in talent shows, was singing and playing guitar, singing primarily (songs by) B.B. King and Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson.

And people began to notice, as Boykin recalled with a smile.

“(When I was) learning to play, my next-door neighbor said that when he came home from work, ‘you were making all that noise on the guitar, but after a few weeks, man, it started sounding good!’ I learned real fast. Like I said, I had been playing for five years so I just had a natural musical sense, I guess.”

Boykin picked up the guitar around the beginning of his high school years, but by graduation he was already a regular at local clubs.

“My whole senior semester in high school, Joe Johnson’s band played, and I played guitar,” he remembered. “But when we (played) for Jack Ruby, we didn’t play at all. We just sang the blues. He would hire us to come over and do shows on Friday and Saturday nights and just sing. We were kind of the floor show, they used to call them – we were performing for Jack while we were still in high school.”

The Scene

Boykin said the sheer number of quality clubs hosting live music in Dallas supported his passion – and that of many other musicians.

“The La Vista, the Club Sands, the Red Noodle – they’re all kind of around the south side of town, around Fair Park,” he said. “It was like it was like a meeting place – you could go there to see music, but there was no dancing and no liquor (sales). You’d have to bring your own bottle, and you could buy what they call “setups,” which was a bucket of ice with some limes and maybe some Cokes and stuff. The cover charge was like a dollar and a half or something when I started playing there in 1957; they only paid us five dollars a day until we got a raise up to eight dollars.”

But it wasn’t just the clubs where these musicians thrived.

“The American Woodman Hall (on Oakland Boulevard, now Malcolm X Boulevard) had a Sunday jazz event that that ran for 17 years,” Boykin remembers. “Just about all the best jazz musicians of that era played at the (Woodman) because they, at three or four o’clock every Sunday, they had the most incredible jazz concert.”

That concert often morphed into a jazz session that would attract everyone.

“At the time, a lot of the white musicians who were students at the University North Texas in the music program, they would come in and sit in with us. Sometimes they would bring some of their arrangements and we would play.”

The Show

The South Dallas Pop Festival started with a conversation between three musicians and a businessman, trying to showcase local talent. Boykin, with the help of other talented bands from the thriving scene came together to put on a local music showcase, but something else helped put the show together: Friendly competition.

“Apollo Commanders and the Soul Seven were kind of at war with each other, and they were two of the hottest bands around.” Boykin explained. “Wendell Sneed, Wayne Money and I – the three of us were musicians, and there was another guy named Allen Thornton. Allen called himself a capitalist. He was kind of a facilitator, (a) very smart guy. The four of us got together, planned and executed that festival at the first Central Forest Club.”

But the talent in Dallas at the time needed a spotlight. Boykin said New York, Nashville, Los Angeles and Toronto were the four music centers in North America.

“If you don’t live in one of those places or if you don’t move to one of those places,” he said, “it is very difficult to launch a career.”

He said he is glad Texas has proved its importance in the music landscape in subsequent years.

“Now, Austin, Texas has risen up, (and) Austin is a great music city,” he said. “I attended Huston-Tillotson College, and I got exposed to the Austin music scene and met some great musicians from that area.”

The importance of those major markets presented the opportunity to showcase something different.

“A lot of the great jazz musicians moved to Los Angeles or New York; the country musicians moved to Nashville,” he said. “You had to, to be discovered, because that’s where the major record labels were located. That’s why that South Dallas Pop album was so important because it documented what was happening in a minor music market.”

The Teacher

Boykin taught for more than 16 years at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts in Dallas. Even now, his passion to teach music remains.

“I tell some of my students now, I’m self- taught, but I had a great teacher,” he said. “Only I knew what I wanted to learn, and what I needed to learn. My teachers were the people who made records. I transcribed stuff off a record. In one year, I could play everything B.B. King had recorded. I bought every one of his records and wore them out. I played both sides of them until I learned every note on the record that he played, and the inflections as well. Not just the note, but how he played the note, how he emphasized the note. B.B. King was my first teacher!”

He said one key instruction he tells students is to “read” a recording just like you’d read a book.

“Music is not for the eye – it’s for the ear,” Boykin said. “So many of the greatest musicians never learned to read (music), or couldn’t because they were blind. I knew what I wanted to learn and what I wanted to play. I wanted to play like the people I heard on the records. So, I’d buy the record, and no matter how long it took me, I would put the good ear on it and work with it until I learned everything that I wanted to learn from that record.”

“When I was coming through, the only school in America that had a jazz studies program was University of North Texas,” Boykin said. “Jazz is not New York’s music. Jazz is America’s music. And that’s true of any of the forms of music; jazz, blues and gospel are branches of the same tree, you know, and they all have some of the same elements. And of course, once the music got to Europe, (you got) the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and on and on.”

The North Texas music scene, uniquely vibrant even then, still nurtures styles of music that other places did not. Roger Boykin has made that music his life.

“When I was 12, I was I was thinking I wanted to go to law school and be a lawyer, but once I got that guitar at 15, I’ve never looked back. That’s been it for me. It’s been all music since then.”

Host Benji McPhail will

Host Benji McPhail will