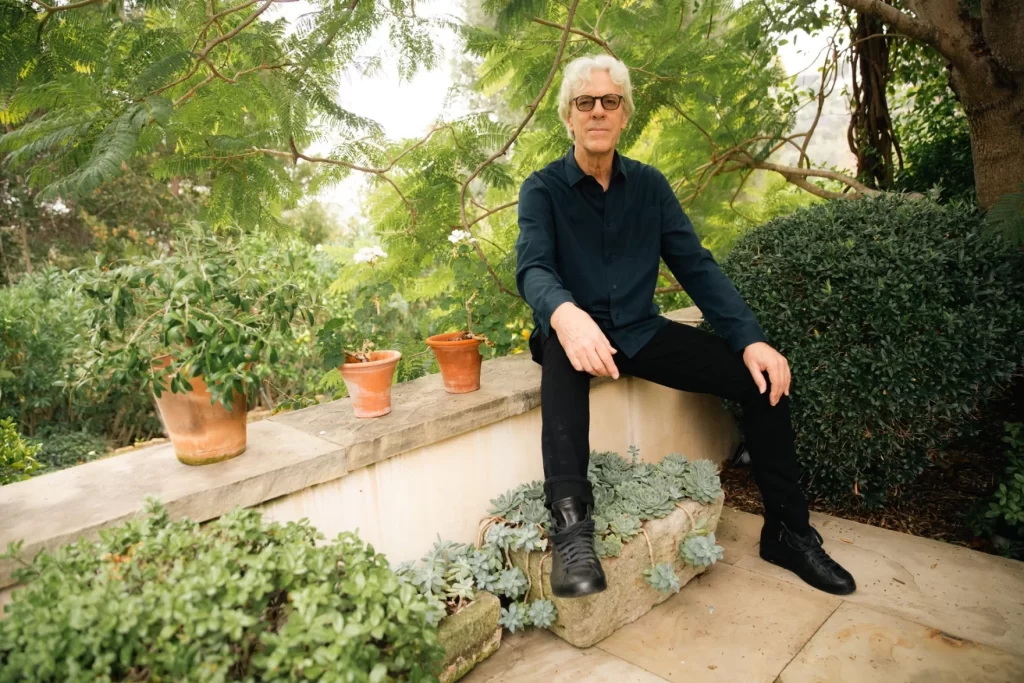

Stewart Copeland was a globetrotter long before he conquered the world with the Police.

Born in Virginia, he grew up in Egypt, Lebanon and London. After settling behind the drum kit with the Police in 1977, Copeland played everywhere from New York’s Shea Stadium to the Tokyo Dome. But he says he holds a special place in his heart for North Texas.

“Dallas-Fort Worth and I go way, way back,” says the 71-year-old drummer-composer. “One of the high points in my life was with the Dallas Symphony at the Meyerson, with those five crazy Texans in D’Drum[in 2011],” he remembers. “The Fort Worth Opera did a brilliant show with my first opera [in 1990]. And I had a great experience doing classes at SMU [in 2012].”

Copeland returns to the Hilltop this month to accept Southern Methodist University’s Meadows Award for “excellence in the arts.” He’ll perform with the Meadows Symphony Orchestra on April 16 at the Meyerson Symphony Center in a concert titled “Police Deranged for Orchestra.”

With the Police, Copeland was one of rock’s jazziest and least predictable drummers — for proof, just listen to “Roxanne.” He’s been impossible to peg ever since, composing for films and dance and writing operas based on the life of Nikola Tesla and the work of Edgar Allan Poe.

I spoke with Copeland by phone from his home in Los Angeles. Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

“Police Deranged for Orchestra” is such an intriguing title. Why’d you call it that?

Before I turned them into orchestral arrangements, I took the band’s recordings and carved them up into unholy shapes. I put this verse with that chorus, and this bass line with that song, and generally scrambled up the Police material. It wasn’t so much an arrangement or a mashup as a de-arrangement.

You’ve taught countless students over the years. When you were a student, did you have a teacher or mentor who inspired you?

I had an entire mentorship in one moment. I was majoring in music in college, and the homework one night was to write 16 bars of music [for piano] with certain rules of harmony. Of course, I already had tons of music. I’ve always been composing. But I can’t play piano. I can’t play “Mary Had a little Lamb.” So I found one of my pieces and adapted it to this homework exercise, and I brought it into class. The teacher plays all the pieces by the other students and says, “This is fine.” Then she comes to my piece and plays it and says, “Stewart! This is actual music!”

There I was, the runt of the litter at the back of the class, just barely able to keep up with all these other students who’d been playing piano all their lives. It might sound like faint praise, but boy, that moment was enough to set me on a career in music.

Since the Police split up in 1986, you’ve been composing for ballet, opera and TV, but mostly for film. How does film work differ from composing for rock ‘n’ roll?

For me, in a rock band, I just bang s—, and if I’m writing songs, I hammer them out on a guitar with my three or four chords that I know. I did write the original songs for the Police, but then as soon as Sting got in the saddle with Andy Summers and harmonic sophistication [developed], that’s when the hits started to come.

I humbly submit that the film composer is not an artist, really. He’s a craftsman in the service of the art of the director. He’s a musician with the widest set of skills in all of music because he has to go where the boss points him. If the boss says, “I need you to do some Rodgers and Hammerstein-type stuff here,” well, I don’t even like Rodgers and Hammerstein, but I gotta study up and figure out how to create that atmosphere.

My first film was a big breakthrough. Out of the blue, I was called by Francis Ford Coppola to score his [1983] film Rumble Fish. And I had no idea how you do that. He was my mentor. He taught me how you create music for a specific purpose and turn it into a very sophisticated emotional landscape. “Tell the audience to be afraid here. Tell the audience that this is a joke.” He turns around one day and says, “This is all really great, but it needs strings.” So these string players come in, and oh my God, it was just so beautiful to hear those chords I couldn’t really play properly. I was transported. And thus began a 40-year journey with the orchestra.

You had a unique childhood. Your dad was a member of the CIA, and you grew up in Cairo, Beirut and London. How did living in all those places influence your drumming in the Police?

It had a pretty big effect. You could call me a “diplobrat.” I had left America when I was 2 months old and I didn’t get back until I was, like, 18. America was a shining city on a hill for me. I was the most patriotic American alive, because I never saw the place. But as I was desperately trying to be American, the music of Arabia surrounded me. It just went into my DNA without me even knowing it.

By coincidence, Arabic music shares some fundamental building blocks with reggae, of all things: They both emphasize the third beat of the bar, whereas all American music is “1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4.” When I was in London in 1977, punk rock was blazing away, but the DJs would chill things out sometimes with dub reggae. Topper Headon of the Clash was the first skinny white kid in the class to attempt to play reggae. But he had to learn it, while it was immediately a piece of cake to me. I could just have fun and run circles around it because it was already part of my rhythmic DNA.

You kept pursuing world music, going to Africa to record “The Rhythmatist” [1985] before Paul Simon went there. And you won Grammys in 2022 and 2023 for your work with Indian composer Ricky Kej. What’s your take on the term “cultural appropriation?”

Cultural appropriation comes in many shapes and forms, and some of it is wrong, like when you take textiles made in Nepal, and make lots of it and sell it at Nordstrom for a fortune without compensating the source.

Nobody — white, Black, yellow, red or green — can play American music without having appropriated from Black culture. The most significant feature of our music derives from Black culture, the backbeat, which was invented in 1898 by one Dee Dee Chandler, who invented the most important instrument of the last couple centuries, the bass drum pedal. That’s where the backbeat and the groove came from, in jazz, rock, funk, soul, rap, all of it. So when it comes to cultural appropriation, any American musician is taking artifacts from Black culture and, in my own case, from Arabic and Jamaican culture as well. So I’m [guilty]. String me up now.S

You recently described a recording session with the Police as “a combination of those two guys being impatient and me being lazy, which means we only do a few takes and then I go hit the pool.” Did you guys really make records that fast?

Well, not every song. We spent days on some songs, like “Every Breath You Take.” But most tracks, by far, were achieved very quickly. Sting would show Andy the chords and the riff, while I’m listening and tapping my knees. “OK. Let’s do a take.” And whatever I’d come up with right then and there is the record for eternity. The drums are locked in, whereas the guitar and bass and vocals, they get to redo all that to perfect their parts.

The upside is that “Stingo” had very little opportunity to get in my grill, although he had a tougher and tougher time with compromise in the band, because he really did have a complete vision of the music. But in this context, because he was impatient and I was lazy, it actually saved a lot of conflict for us to work that quickly.

You’ve explored so many areas of music. What do you want to accomplish in the future?

Well, there are not that many people left in the world that I need to impress, except for my siblings. Sting and Andy will always be those older brothers that I need to impress.

People say, “What do you do for kicks? What’s your recreation?” And wow, my work closely resembles a recreation. On my holiday, I’ll probably write an opera. It’s like making model airplanes. I wake up every day and rush through breakfast so I can get back to work, you know? I’m very thankful I found a line of work that lights me up. It never gets old. Here I am, 70-something years old, and music hasn’t even started to hint at getting old.

Stewart Copeland and the Meadows Symphony Orchestra perform “Police Deranged for Orchestra” at 7:30 p.m., Tuesday, April 16, at the Meyerson Symphony Center, 2301 Flora St., Dallas. smu.edu/stewartcopeland

Arts Access is an arts journalism collaboration powered by The Dallas Morning News and KERA.

This community-funded journalism initiative is funded by the Better Together Fund, Carol & Don Glendenning, City of Dallas OAC, Communities Foundation of Texas, The University of Texas at Dallas, The Dallas Foundation, Eugene McDermott Foundation, James & Gayle Halperin Foundation, Jennifer & Peter Altabef and The Meadows Foundation. The News and KERA retain full editorial control of Arts Access’ journalism.

Giveaway: Win weekend passes to Wildflower! A

Giveaway: Win weekend passes to Wildflower! A